THE CLOWN OF THE CLOWNS, DAVID LARIBLE, TEATRO VITTORIA | ROME

The Clown of the clowns, David Larible

National Opening – Teatro Vittoria – Rome

08 – 27 February 2011

Text by Roberta d’Errico

The curtain rings up on the stage full of the whole paraphernalia attaining to the circensian tradition: mirror on the small table, make up for face, masks, gleaming clothing, a piano and many other musical instruments. The soft lighting makes oneiric the ambience of the scene flooded with smoke. The time is halted like an enchantment, in a trip through the centuries. The white clown Gensi is there, played by Estephan Kunz: His face was made-up coherently to the name of his figure, he has the poise and the austere bearing that the tradition seeks.

To the piano a musician starts to play the music, the white clown backs the pianist using a long saw. Who could have ever thought that it can ring harmonious sounds when bent in a particular manner. Still the clowns are able to set the objects up to life, to make them spring unthinkable things for us.

A new character arrives on the stage: here it is, David Larible, in the cleaner’s shoes a little bit unprepared and clumsy, his presence is bothering the musical performance of the white clown. A contested relation is coming out in the light between the white clown and the one that will become the stately clown in a short time. The cleaner wishes to share that magical world because is spellbound for the objects put on the stage. He tries to play an instrument any time he is alone on stage far from the white clown’s stern look, but as soon as Gensi reappears he deprives of it. At the end with no instruments to be played our character makes music by a small accordion which has been hidden in his mouth, but the white clown’s attempts to prevent him from playing it, causes his swallow of the instrument. So we witness the first clear quotation of Chaplin’s world with Larible hiccupping at the music of the accordion, just like Chaplin was hiccupping at the music of the whistle in Luci della Città (City Lights, 1931).

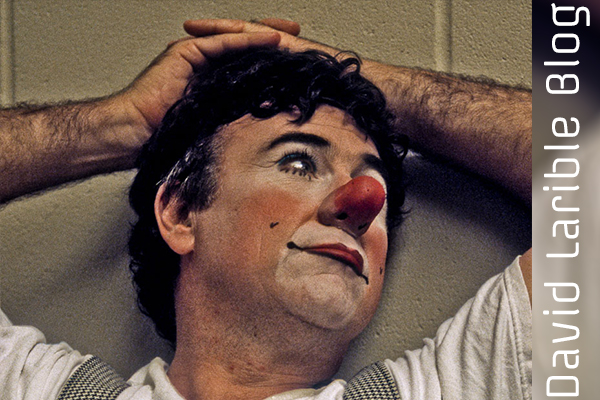

Again alone on the stage, Larible initiates some conjuring tricks executed through invisible objects with the cooperation of a person from the audience and supported by his extraordinary mime. Our cleaner decided to be a real august clown, but this is possible only if he demonstrates to Gensi he has histrionic attitudes and ability to be a standing joke. So we attend to an initiation rite and notwithstanding the white clown’s hesitations, the ceremony of taking the true and real habit of a stately clown can have a start. And then Larible takes a sit at the make-up small table and at the music of Vesti la Giubba , played by Gensi, very famous aria from Mascagni’s opera Pagliacci, he transforms himself under our eyes: red nose, made-up face, hat, large and strange clothes, great shoes. The scenery got a double implication: it seems that the gift to make somebody laugh is a inward necessity and on the contrary who is not able to express himself get overcome by sadness.

The first half of the performance comes to a stop and the second one begins with the predominant audience interaction. The mastery of the stage and the knowledge of all the aspects of the performance appear in such a phase when Larible has no problems to involve even the children who feel at their own ease with gag that have the simplicity of the complicated things.

Now Larible offers a poetic solo. The curtain is lowered and he is on the stage-box. The lighting is dimmed and an ox eye is on. Larible begins a funny fight with the light, he tries to put it away from him but it comes back. Now Larible plays with it like in a play with a ball. It is possible to recognize in his movements the exact reproduction of those performed by Chaplin’s motion picture Il Grande Dittatore (The Great Dictator, 1940) when he plays with the map of the world. The turn comes to an end when Larible captures the light and makes it fall in a bucket.

The performance goes on with involving the adult and the younger audience, grouped on the stage. Larible shows his capabilities to manage unexpected and unforeseen events with people unaccustomed to be on stage not knowing of being able to play roles and interpretations.

Larible is able to make sure that each of the chosen person, will take a little bell (in spite of the white clown’s warnings not to touch them) and sound it, at his signal, backing the piano music. The performance grows rich with a great involvement of the audience when Larible entrusts the improvised helpers with different unusual and strange instruments, becoming in so doing the conductor of the grotesque characters forming the particular orchestra. The meaning of the performance seems to be just this one: we can see it by our eyes the passage from normal to exceptional situations.

And again Larible involves three young fellows of the audience, giving them some recommendations, that he is successful in doing them mime by mouth the singing and by gestures the passions and the feelings of some aria of opera acting a sort of puppet living theatre in which he is the master who moves the people invisible threads.

The performance is coming to the end. The stately clown finished his time, must go back to being a cleaner. There is sadness in the atmosphere. The white clown is on stage and watch the stately clown undressing. The movements that Larible does, in taking off his own make-up, in looking at himself in the mirror with melancholy, calls back to the memory the scene of Luci della Ribalta (Limelight, 1952) in which Chaplin/Calvero looks himself in the mirror and takes off his own make-up with a look of despair. In this latest case the despair of our stately clown originates from the lost ability to raise a laugh as far as the world doesn’t feel like to raise a laugh any more.

But then the white clown begins playing and singing the Charlie Chaplin’s song with which the motion picture Tempi Moderni (Modern Times, 1936) got to an end. The stately clown is by the time in his usual clothing, he is sad and depressed, but it is just the white clown that neglecting his traditional severity guise, get near him and make him understood that he must not loose all hope, but smile. And thus, smiling and arm in arm, just like the final scene in the motion picture, Gensi and Larible leave the stage together with their backs to the audience, because the smile goes beyond the performance, because if we smile in our life we will love to smile even on the stage.

When the curtain is lowered, Larible comes back on the stage having no scene dress on, now, just to greet the Rome audience, capital city of his native land and with Gensi sing the Nicola Piovani’s song Quanto t’ho amato. A debt of love to our Country and for a world full of magic, of music and of feelings in which the words have no matter.

Roberta d’Errico

Theatre Editor

000

000